Confessions of an olive oil virgin

Written by David Illsley

Just sit back and malax.

Can I just ask: does it make your day too, to come across a cool new word like malax? Socially, you probably get out more than I do, but even so, you’ll have to agree that malax, or malaxate, to give the alternative spelling, has a certain allure, a certain degenerate intrigue to it. Or is that just me? But the thing is, as a newbie olive oil producer, or oleocultor as the locals say, it’s a term you have to understand.

Dios mio, there was (and is) so much I didn’t know about olives. Baby stuff. Did I honestly know back then, hand on heart, that if you leave green olives on the tree then they slowly become black? (They do, by the way.) You could just as well have told me that if you leave 7Up for long enough then it turns into Coca Cola. (It doesn’t; I just checked.) But the point is, I knew nada about the process, and had to pretend otherwise.

So, in the remote case that any of our readers should be similarly naïve, I thought I’d walk you through the basic procedure:

Though olive trees – olea europaea – can last famously for centuries, as saplings they are no slouches, and can begin bearing fruit within as few as three years. They need watering, of course, as it’s almost a given that where there’s enough sunlight for them to thrive then there’s likely to be little annual rainfall; that’s certainly the case in the alpujarras. They also require nutrition, ideally something which has passed first through the bowels of domestic livestock. They also need pruning, first to let in light to the middle of the tree, and second to eradicate the annoying and energetic shoots which emerge each year from the main trunk. These latter are known locally as mamones, a term which my elderly farmer-neighbour-tutors seemed always especially keen for me to use…..and even now I blush, since yes, although it does indeed refer to an appendage of new growth, it also means something terribly rude; I’ll let you Google it. I mean, how was I to know?

Come the Springtime and the branches are teeming with flowers. On a tree of such noble lineage you might expect something majestic, but in fact the flowers are dinky, so insignificant that you have to look twice to see them. But insects adore them, and they pack a whopping pollen- punch, especially to the hay – fevered hooters of the anglo-saxon. And so the incipient fruit sit there, humming with bugs, swelling all through the Summer, changing colour as they ripen.

As Spain is by far the world’s biggest producer of olive oil, most of the mass production is now both efficient and highly-mechanised. Those are not necessarily the terms you might choose were you to observe our own clumsy efforts, but the underlying principles remain the same. First, whatever your methods, the tree has to be shaken in order that the fruit fall to the ground. You can employ various means to this end: tractors with eccentric motors, a system with vibrating clamps, or motor-driven, oscillating silicon fingers. We use a couple of sticks.

And as such I’m always vaguely reminded of skiing. Don’t mock: at this altitude we harvest late, usually January, when there is always snow on the peaks just above; the days are short but filled with blessed blue skies, and all around is that distinctive, nostril-burning smell of true cold, and the squinting brilliance of mid-Winter sunlight. For many of our volunteer pickers a welcome by-product is the acquisition of a deep skier’s tan. Perhaps less welcome is the knowledge that – again like skiing – in just a few short hours your body will begin to ache in places you didn’t even know you possessed.

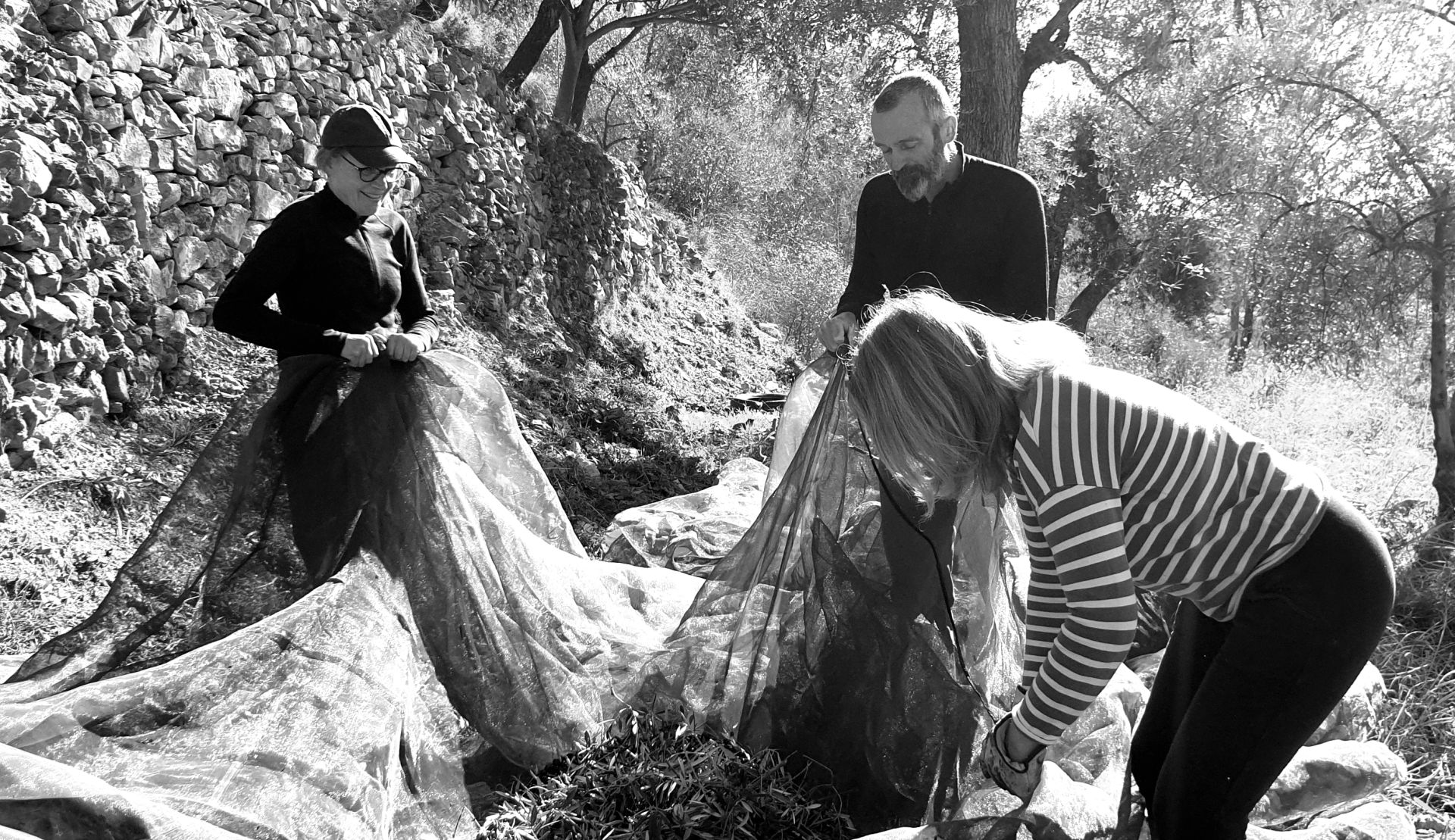

But sooner or later you’ll be rewarded with a floor full of your lustrous, elliptical bounty. They land in a net, which if you twitch it, makes the olives jive, so that the image of a fisherman’s haul is hard to ignore.

And thus into sacks, whose size in these parts is a clear indication of a chap’s virility, followed by a loose sieving to remove excess leaves, twigs, nests, the belly-button fluff of assorted squirrels and any other redundant tree-stuff. Next comes the weighing -in, an event marked by much bickering and the source of grudges going back generations.

Until finally, the whole lot is thrown into a large steel drum. The whole lot, mind, in other words the whole olive, including the skin and the stone in the middle. And here, inside the drum, is a dull blade, which rotates slowly, so that the contents are at last ………malaxed. (See! I knew we’d get there in the end!). The dictionary defines this as an act of slow churning, specifically in relation to the milling of olives, so sadly it’s not a term you can use every day, though Spaniards everywhere will no doubt recognise Almazara, the word given to an olive press; you’d have to conclude that the two are etymologically linked.

The mixture sits there for ……a while, let’s say, just the right amount, depending on the artisanal skills of the person in charge, but not for more than a couple of hours. In Mairena this brew is kept at room temperature, resulting in the fabled cold-press variant. A boffin would tell you that the temperature affects the phenol content and the residual peroxide values; I prefer to trust the instincts of Adolfo, the owner.

This malaxed paste is neither pretty nor flavoursome, with the consistency of a lumpy yoghurt, and the colour of Bovril. It’s now spread thickly onto individual circular mats made of coir (coconut) fibre and esparto. Think of a straw frisbee, about a metre across. These are then stacked vertically, and trundled into a metal frame, at which point they are squashed together, top to bottom, using a huge hydraulic jack The power for this in Mairena is provided by two aged motors, painted lawn-mower green, with original brass camshafts and tappets; remember your lonely Uncle X, the one who enjoyed the traction engine displays at the village fete? He would have loved these. They were certainly built to last, and with a pleasing industrial aesthetic rarely seen these days, and make a din to scare the angels.

At this point, treacly dollops of goo, to use the technical mot juste, begin to trickle down the outside of the cylindrical stack of mats. Imagine the excess ketchup, if you will, on a Homer Simpson multi-decker-burger. This highly viscous fluid is then collected in a settlement tank, having been washed and mixed – quelle horreur! – with plain old H2O. This sounds so weird, and yet is the best solution, pun intended. Oil, of course, is by nature less dense than water, and will eventually make it’s way to the surface and float, thereby trapping any particles or impurities in the precipitate residue at the bottom of the container. Which is why, incidentally, so many of the clay amphorae you see strung up as decoration on the walls of restaurants across the mediterranean have a kind of pointed bottom part, and won’t stand up by themselves, but require a special stand to stay upright, for this pointy part is a kind of terra cotta sump, where all the oleaginous crud could accumulate.

You need time for this to happen, usually at least a year, and patience. But it’s worth it. Week by week the silt is drawn off from the very base of the vessel, and dumped, for it is considered to be essentially worthless, at least round here it is, and worthy only of a dreaded second-pressing. Shudder !

Is it such a bad thing to be a nouveau olive snob?

https://www.instagram.com/laschimeneas/?hl=en

Tagged under: